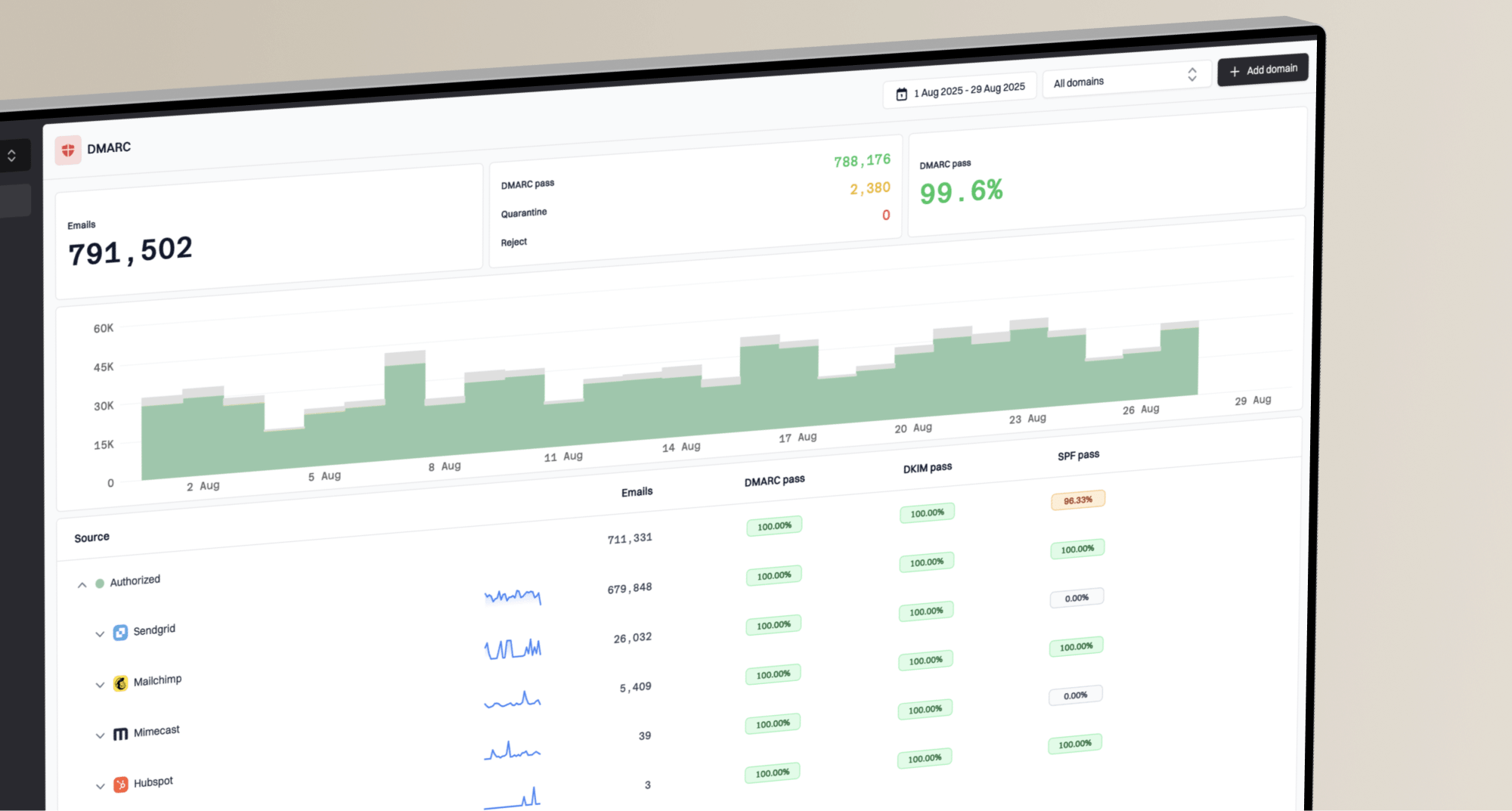

Email authentication can feel like a solved problem. You set up your SPF, DKIM, and DMARC records, and everything should just work. For the most part, it does. However, the real world of email deliverability is filled with nuances and implementation-specific details that can cause major headaches. One of the most common sources of confusion I see comes from how major mailbox providers, like Microsoft 365, handle these authentication standards.

Specifically, Sender Policy Framework (SPF) seems straightforward on paper but can be a source of intermittent and frustrating delivery failures. You might have an SPF record that looks perfectly valid and passes all the online checkers, yet you still see strange failures when sending to users on Microsoft Exchange Online. The reason often lies not in your record itself, but in a hidden constraint within Microsoft's infrastructure: the way it performs DNS queries.

Before we dive into the Microsoft-specific details, let's quickly recap what SPF does. At its core, SPF is designed to prevent email spoofing by allowing a domain owner to specify which mail servers are authorized to send email on their behalf. This is all done through a simple TXT record published in your domain's DNS.

When an email is received, the receiving mail server looks at the sender's domain in the `Return-Path` address. It then performs a DNS query to find the SPF record for that domain. The server compares the IP address of the machine that sent the email to the list of authorized IPs and servers in the SPF record. If it matches, the SPF check passes. If not, it fails, signaling that the message might be fraudulent.

The SPF specification has a critical limitation: it must not result in more than 10 DNS lookups. Each `include`, `a`, `mx`, `ptr`, and `exists` mechanism in your record counts towards this limit. If your record requires more than 10 lookups to resolve, it will return a permanent error (`permerror`), making it invalid. This is a common problem for organizations that use many third-party services to send email, as each service adds an `include` statement.

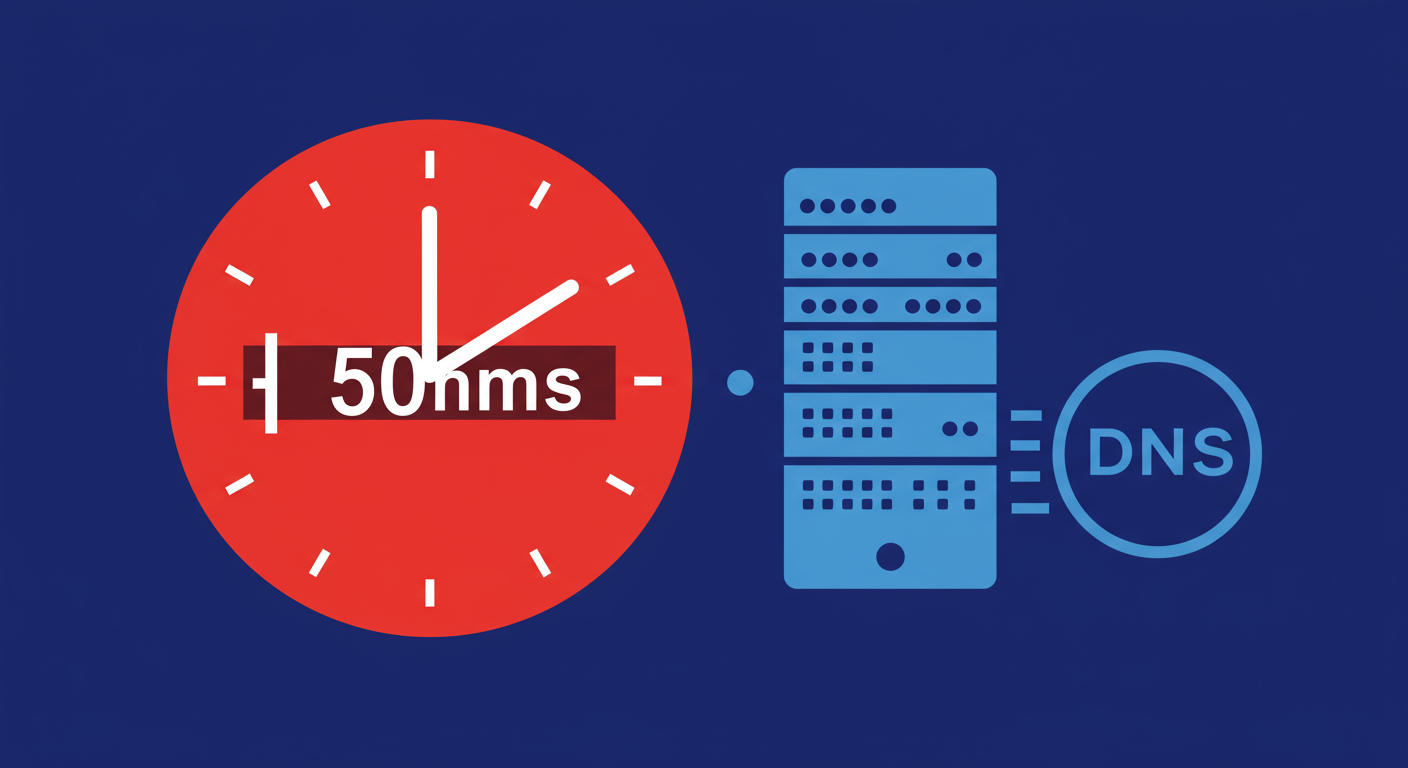

While the 10-lookup limit is a well-known part of the SPF standard, Microsoft introduces another, less-documented constraint. As some have discovered through trial and error, Exchange Online Protection (the email filtering service for Microsoft 365) uses a very aggressive internal timeout for each DNS lookup it performs during an SPF check.

This timeout is reportedly set to just 500 milliseconds. If any single DNS query needed to resolve your SPF record takes longer than half a second, Microsoft's server will treat it as a temporary failure (`temperror`). This isn't for the entire SPF evaluation, but for each individual lookup within it. If your SPF record includes a service whose DNS servers are slow to respond, it can trigger this timeout, even if your record is perfectly configured.

This behavior is an implementation detail on Microsoft's side, likely to protect their own systems from performance degradation caused by slow external DNS resolvers. However, it can cause intermittent SPF failures that are incredibly difficult to diagnose. One moment your email is delivered, the next it fails an SPF check, all because a DNS server somewhere was a few milliseconds too slow to reply.

The result of a DNS timeout is an SPF `temperror`. Unlike a `permerror`, which indicates a permanent problem with your record's syntax or lookup count, a `temperror` suggests a transient issue. Most mail servers are designed to treat a `temperror` as a neutral or soft fail result. The message might be delivered, but it could be subject to greater scrutiny and more likely to land in the spam folder.

Where this really becomes a problem is with DMARC. DMARC requires that an email passes either SPF or DKIM and that the domain in the `From` header aligns with the domain used for the passing check. If SPF returns a `temperror`, it fails the check. If DKIM also fails or isn't aligned, the entire message will fail DMARC authentication. For domains with a `p=reject` policy, this means the email will be blocked, all because of a brief DNS delay.

You can't change Microsoft's timeout, but you can optimize your SPF record to be as fast and efficient as possible, minimizing the risk of triggering it. The goal is to reduce both the number of DNS lookups and the dependency on potentially slow third-party DNS servers.

Here are some practical steps you can take:

v=spf1 include:_spf.google.com include:mail.zendesk.com include:servers.mcsv.net include:spf.protection.outlook.com -allv=spf1 ip4:1.2.3.4 include:spf.protection.outlook.com -allUltimately, managing an Office 365 SPF record effectively means being proactive. Don't just set it and forget it. Regularly review your record for efficiency and performance to ensure your legitimate emails aren't being caught by an obscure, provider-specific timeout.

Understanding how different receivers interpret email authentication standards is a huge part of achieving good deliverability. The Microsoft 365 SPF timeout is a perfect example of a hidden rule that can have a real impact on your sending. It underscores the fact that a technically valid record isn't always enough.

By keeping your SPF record lean, prioritizing direct IP mechanisms, and being aware of the performance of your third-party providers, you can build a more resilient authentication setup. This approach will not only help you avoid Microsoft's 500ms timeout but also make your overall email program more robust and less prone to unexpected failures from either blacklists (or blocklists) in the future.